Chili, black pepper, white pepper, and Sichuan pepper

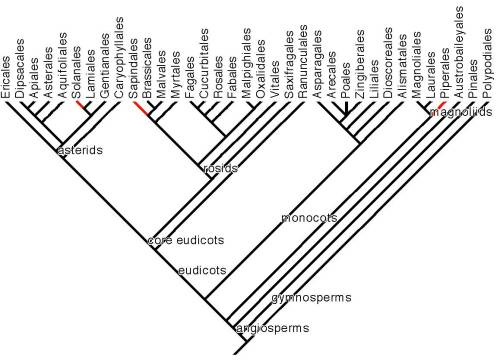

Black pepper, pink peppercorns, chili pepper, Sichuan pepper – except for being “hot,” these spices have as little in common as Sergeant Pepper and Pepper Potts. Their homelands are scattered across the world, and they were spread through distinct trade routes. They are not closely related; they belong to families about as far apart as possible on the phylogenetic tree below. They even aim their heat at different sensory receptors in your mouth.

Phylogenetic tree of taxonomic orders containing food plants. Branches of orders with different “pepper” species in red: black pepper in Piperales; pink and Sichuan pepper in Sapindales; and chili peppers in Solanales. For more information about what the labels on the branches mean, how to read the tree, and how all these orders fit in the evolutionary history of plants, see the phylogenetic tree view of our food plant tree of life.

There is an obvious distinction between the two main culinary categories of pungent pepper. One is the long-time companion of salt, living beside it in shakers or grinders, and carrying a whiff of the old-world. The other is bright and lip-burning hot, sometimes dried, sometimes pickled, sometimes called by its new-world Nahuatl name, chili. Or chilli. Or chile.

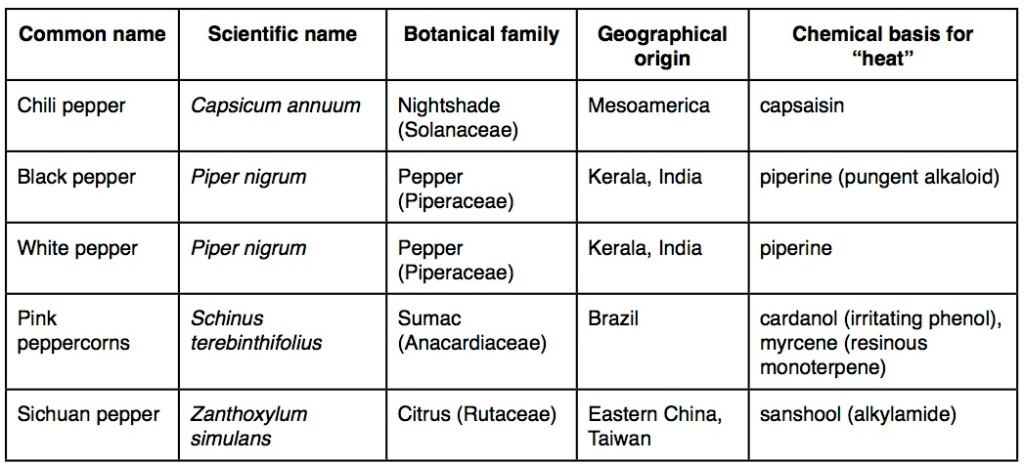

The first kind of pepper – the pepper-grinder kind of pepper – is most often just ordinary black pepper, but there are other kinds of small, round, grindable pepper, such as white, green, pink, and Sichuan varieties. White and green pepper are just variations on the usual treatment of black pepper. For example, white pepper, with its distinctive wet-dog taste, is the seed left behind when the black pepper berry is allowed to rot away. By contrast, pink and Sichuan peppercorns are entirely different species.

Black pepper plant

Schinus molle

Black, white, and green pepper all come from a tropical woody vine, whose fruits (eventual peppercorns) develop close together in long narrow clusters along the flowering axis. The species is Piper nigrum (specimen from the National Arboretum in Washington, D.C. pictured at right), and it seems to have originated near the southern tip of India in Kerala. There is also an uncommon version of black pepper that comes out pink, but the common pink peppercorns grow on a Brazilian tree from the same family that gives us poison ivy, cashews, mangos, and pistachios. The full species name is Schinus terebinthifolius, which sounds like a medical term for a socially debilitating degree of timidity. On the contrary, the Brazilian peppertree and has become an aggressive weed in Florida and other states. A close relative, Schinus molle, grows widely in California, and is pictured to the right. Sichuan pepper comes from the species Zanthoxylum simulansin the citrus family and is produced by a small, shrubby tree native to eastern China and Taiwan. It is one of the five spices in Chinese five-spice mixture.

Chili pepper plant

Finally, cayenne pepper and most other hot chili peppers are varieties of the species Capsicum annuum, a species in the nightshade (tomato/potato/eggplant) family Solanaceae (pictured at right). C. annuum is extremely diverse and includes mild sweet varieties as well. These peppers originated in the Americas, probably in southeastern Mexico (Aguilar-Melendez et al. 2009), and were probably domesticated several different times by several different groups beginning around 6000 years ago. They grow on small plants which can get a little bit woody but never get very large.

To see just how distantly related these peppers are, look at their placement on the phylogenetic tree of botanical orders above (use the table below to help you keep the different pepper types straight). They fall into the orders Piperales (black pepper), Sapindales (pink and Sichuan peppercorns), and Solanales (chili peppers). Although both pink and Sichuan peppercorns belong to the Sapindales, they are not particularly closely related within that group.

Again, the main thing that these peppers have in common is that we use them for their heat – yet they don’t even feel hot for the same reasons. The neurobiology underlying the heat sensation is slightly different between black pepper, Sichuan pepper, and chili peppers. Peppercress (from the mustard family) is hot for yet another reason, but that’s a topic for another time.

We have a system of nerves in our head (trigeminal somatosensory neurons) that detect temperature, touch, and chemical stimulation. The nerve endings are particularly dense in our noses and mouths, where they are thought to help us detect noxious chemicals, sharp bits of food, and extreme temperatures that would damage our mucous membranes. These neurons send sensory information to our brains when temperature, pressure, or chemicals trigger specific ion channels to open (Gerhold & Bautista 2009, Viana 2011).

When we say that hot chili peppers are hot, we mean it: their chemical irritant capsaicin triggers an ion channel that normally responds to moderate heat (TRPV1), sending a signal through our trigeminal nerve and making our brains believe we are being warmed. Capsaicin then amplifies its own effect by making this receptor sensitive to lower temperatures; a sip of tea or a splash of warm tap water suddenly feels dangerously hot. Interestingly, birds are not bothered by hot peppers because their version of TRPV1 does not bind to capsaicin. Some people mix hot chilis into bird seed to repel capsaicin-sensitive squirrels from feeders without bothering the birds.

Black pepper produces piperine, which works slightly differently. Piperine triggers the same temperature-sensing TRPV1 channel as capsaicin, but it also triggers the TRPA1 channel. This second channel responds to a wide array of pungent foods, including clove, hot mustards (like wasabi), cinnamon, garlic, and ginger.

Sichuan pepper works through a more complicated set of receptors, which may explain its complex sensation. Its effect comes from a molecule called hydroxy-α-sanshool, named for a close relative called sansho (Zanthoxylum piperitum). Not only is sanshool mildly “hot,” but it causes the pins-and-needles feeling that comes when a limb is coming back after falling asleep. It’s like hitting your funny bone and feeling it in your lips and tongue. The Sichuan pepper feeling can also take a full minute to register, much longer than the response to hot chilis and black pepper.

Some evidence suggests that sanshool triggers both TRPV1 and TRPA1, like piperine does, but it doesn’t have to. Researchers have bred mice that lack both of those receptors, and some of them were put to work in a study by Lennertz et al (2010). Mice were allowed to drink water without sanshool for a few days before sanshool was added. All the mice drank the peppery water as normal for about 50 seconds, until they were able to detect the sanshool, and then they pulled away. This was true whether mice were normal or lacked the capsaicin and piperine receptors, indicating that some other receptors must be responsible.

It turns out that sanshool does not work primarily by fooling the body into feeling heat. Instead, it excites neurons that sense extremely light touch. This tingle-inducing compound works through the same kind of ion channel (two-pore potassium channels) as some anesthetics, and so may have a similar biological basis (Bautista et al. 2008).

The taste of pink peppercorns has not been investigated from a neurobiological perspective, and it’s probably not high on the list of spices to test, since they are not so much “hot” as bitter and irritating, with the potential to cause allergies in people sensitive to poison ivy and its relatives.

There is much more to the full pepper experience than tingling or burning. First, there is our perception of the pepper. Peppers of all types work their magical powers through the trigeminal nerves, which are completely separate from the nerves that convey taste and smell to our brains. The flavor of pepper arises from “hot” piquance in combination with basic taste, and smell. Second, there is the pepper’s own experience. What role do these compounds play in the life of the plant? Not much ecology has been done to test this question in black and Sichuan pepper, however it appears that capsaicin protects wild chili seeds from fungal infection (Tewksbury et al 2008), deters seed-eating mammals, and encourages capsaicin-tolerant birds to disperse its fruit (Levey et al. 2006). Smart peppers.

Chili varieties of course vary tremendously in capsaicin content, as well as other fruit qualities that affect flavor of foods. Michelle uses two different dry chili varieties in her amazing and simple hot sauce recipe, which you can learn about in this video. Put this beautiful red sauce on your table next to the black pepper, and the next time someone asks you to “pass the pepper,” share the fascinating chemistry of these dried fruits from far-flung branches of the plant tree of life.

Aguilar-Meléndez, A. et al. (2009) Genetic diversity and structure in semiwild and domesticated chiles (Capsicum annuum; Solanaceae) from Mexico Am. J. Bot. 96:1190-1202; doi:10.3732/ajb.0800155

Bautista, D.M, et al. (2008) Pungent agents from Szechuan peppers excite sensory neurons by inhibiting two-pore potassium channels. Nature Neuroscience 11:772-779 doi: 10.1038/nn.2143

Gerhold, K.A. and D.M. Bautista (2009) Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Trigeminal Chemosensation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1170: 184–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03895.x

Lennertz, R.C. et al. (2010) Physiological basis of tingling paresthesia evoked by hydroxy-α-sanshool. J Neurosci. 30: 4353–4361. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4666-09.2010

Levey, D. et al. (2006) A field test of the directed deterrence hypothesis in two species of wild chili. Oecologia 150: 61-68 doi: 10.1007/s00442-006-0496-y

McGee, H. (2004) On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Scribner, New York.

Tewksbury, J, et al. (2008) Evolutionary ecology of pungency in wild chilies PNAS 105: 11808-11811 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802691105

Viana, F. (2011) Chemosensory Properties of the Trigeminal System. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2: 38–50. doi: 10.1021/cn100102c.

Link:

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário